Is it Time to Decouple from Petroleum?

Bio-polymers have entered the market, and demand is expected to grow rapidly over the next decade.

Bio-polymers have entered the market, and demand is expected to grow rapidly over the next decade. According to the European Polysaccharide Network, capacity for bio-based plastic will increase from 0.36 million tons in 2007 to 2.33 million tons in 2020, and some companies are taking this opportunity to introduce new products. For example, Innovia has reinvented cellulosic film with its Natureflex™ line. Coatings and engineering improvements, coupled with a recently capitalized production line, have put this mature product back on a growth track. Corn-derived polylactic acid (PLA) from NatureWorks LLC, a Cargill company, (and others) and Novamont’s Mater-Bi™ are used for films, molded parts, and a variety of other applications.

These are only a few examples of the widespread advent of bio-based industrial raw materials and finished products. We have all heard the adage, “Sure, I want to be environmentally responsible, but not if it costs more money.” Despite this sentiment, the unit costs of the products listed in the preceding examples range from two to five times more than their petrochemical predecessors. So what is the reason for the continued interest in bio-based materials?

It's Environmental Altruism, Right?

According to many, new carbon is better for the environment than old carbon. Vinçotte, developers of the OK Biobased certification labeling system, explains the significance of bio-based material in the documentation on its website. In summary, the consumption and release of new carbon does not lead to an increase in the average amount of CO2 present in the atmosphere. This, the theory goes, helps to reduce the warming effect caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite the atmospheric advantages of renewable materials, not everyone is ready to commit to changing. For example, renewability is not yet part of the Wal-Mart packaging scorecard. GreenerPackage.com, Wal-Mart’s packaging data partner, says it is waiting until the Federal Trade Commission provides guidance on what constitutes a renewable resource in the next version of the Environmental Marketing Claims guideline, which is projected to be available sometime in 2010.

Still, the interest in bio-based raw materials persists and has begun to translate into real demand. Frito-Lay and International Paper are two global corporations that recently added bio-based offerings to their traditional product lines (in the form of compostable snack food bags and PLA-coated hot beverage cups, respectively). The desire to improve the reliability and availability of raw materials is driving the move to bio-based raw materials as much-or more-than environmental considerations.

The reliability of petroleum-based adhesive resins has been impacted by fundamental shifts in the global chemical supply infrastructure. New and efficient ethylene production has been installed in the Middle East. As these plants come on-stream, older and smaller facilities in the U.S. and Western Europe are shutting down. Most of the new plants are designed to crack natural gas instead of naphtha and thus will not generate the pyrolysis gasoline byproduct needed as the feedstock for many hydrocarbon products like isoprene and tackifying resins.

Can the Adhesive Supply Chain Decouple?

Fortunately, adhesive producers and suppliers are taking steps to offer alternatives to help improve supply-chain diversification. Choices are available for companies that range in size and scope from global adhesives producers that are interested in large volume and consistent quality for multiple production locations, to specialty adhesive manufacturers that are locked into long-term formulations, to all of those in between.

The list of products based on sustainable materials is growing, and chemistries are available that use raw materials that are renewable within our lifetimes. The adhesive formulators’ expertise allows them to develop products that achieve the required performance while meeting the demands of their and their customers’ supply chain professionals.

Polymers

Polymers give adhesives structure, and the choice of polymers depends on the final end-use application. One particular polymer building block that has experienced supply challenges over the past several years has been isoprene. Isoprene is used to produce polymers for a variety of applications ranging from toothbrush handles to high-performance, engineered pressure-sensitive adhesives. Suppliers of isoprene-based polymers recognize their customers’ sensitivity to the supply volatility, and they are taking steps to develop alternatives.

In addition, many of these same companies are developing polymers based on bio-isoprene, a polymer building block that is manufactured from oilseed waste. In December 2009, Goodyear, in partnership with Genencor, announced the introduction of the world’s first concept demonstration tire based on bio-isoprene technology. Although this technology is still several years from commercial production, Goodyear’s Jesse Roeck summarized the potential of the technology, saying “The development of BioIsoprene™ could make Goodyear less dependent on oil-derived products. We share Genencor’s vision of lessening industry impact on the environment by applying renewable raw materials in the supply chain.”

Polymers in commercial quantities are available for packaging adhesive producers today. For example, NatureWorks produces biopolymers derived from renewable resources. DaniMer Scientific, LLC has taken these polymers one step further; its adhesive developed for packaging applications contains over 99% renewable content.

Oils and Waxes

Oils and waxes are used in adhesives as performance modifiers and processing aids. Many of the products traditionally used in adhesives are subject to disruptions due to petroleum dynamics. Produced as a bottom-stream in the fractional distillation of petroleum, paraffin wax can be captured and further processed to be used in the gasoline pool. As gas prices rise, paraffin waxes become less available. Vegetable oil companies, such as Cargill, are also working on corn- or soy-based oil and wax replacements as alternatives.

Resins

Tackifying resins improve specific adhesion to a variety of substrates. Hydrocarbon tackifiers are manufactured from the byproducts of ethylene and propylene production. When they were originally introduced, hydrocarbon resins were offered as synthetic alternatives to naturally derived resins. At the time, it made sense because they were cheaper and readily available. With more companies focusing on long-term supply sustainability, bio-based resins are now back in vogue as natural alternatives to synthetic resins.

Today, rosin offers a raw materials source that is commercially available in the scale needed and has a positive long-term supply outlook. Rosin’s ester derivatives, rosin esters, are of particular importance in adhesive applications.

Multiple Options

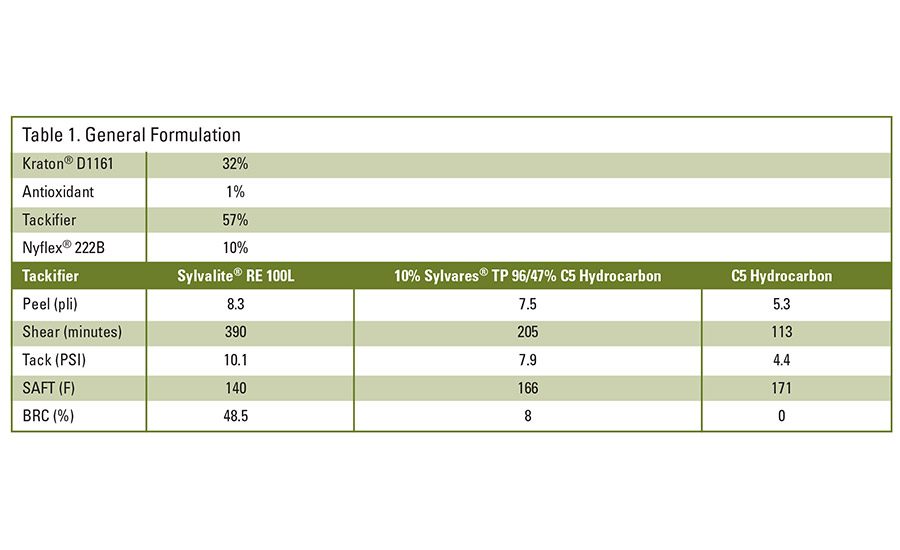

Of course, decoupling is not an all-or-nothing proposition. Replacing just a portion of your adhesive with a supply sustainable alternative helps to reduce your risk. The example formulation shown in Table 1 illustrates how a hot-melt pressure-sensitive adhesive can be economically diversified from what has typically been 0% bio-renewable content (BRC) to nearly 50% BRC. By incorporating a bio-isoprene polymer or a naphthenic oil alternative, the BRC can be pushed even higher.

Industrial companies are planning for a post-petroleum economy. Bio-based raw materials are available for adhesive companies today, and it is likely that the quality, range, and availability of these products will continue to increase.

Editor’s note: PlantBottle™ is a trademark of Coca-Cola; Natureflex™ is a trademark of Innovia; Mater-Bi™ is a trademark of Novamont; BioIsoprene™ is a trademark of Genencor; Kraton™ is a trademark of Kraton Performance Polymers; Nyflex™ is a trademark of Nynas; Sylvalite® and Sylvares® are registered trademarks of Arizona Chemical.

For more information, contact Arizona Chemical Co. at 4600 Touchton Road E., Suite 1500, Jacksonville, FL 32246; call (800) 526-5294; e-mail info@azchem.com; or visit www.arizonachemical.com.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!