Bio-Coatings Improve Implant Functionality

A new coating could help medical implants function better.

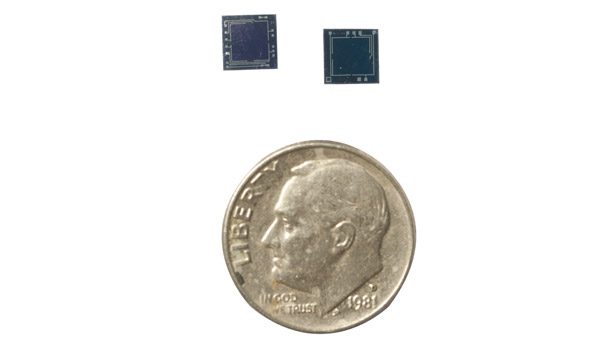

A small sensor like this is used to monitor bodily functions or deliver drugs. Produced by a collaborator group at the University of Technology in Dresden, Germany, the sensors were coated with thin layers of customized block copolymers in Carmen Scholz’ research. (Photo: Michael Mercier/UAH.)

UAH Chemistry professor Carmen Scholz, Ph.D., with doctoral candidate Samuel Nkrumah-Agyeefi and junior Brittany Black in a lab at the Materials Science Building. (Photo: Michael Mercier/UAH.)

Tiny implants to monitor bodily functions or to provide insulin or other drugs based on immediate need would be an advancement in personalized medicine. But a problem inherent in implants is the tendency of the human immune system to recognize the device as an invader and encapsulate it, preventing the device from doing its job.

Carmen Scholz, Ph.D., of The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), has been working on the customized synthesis of biocompatible polymers that can coat sensors that are then implanted into the body to cloak them from the immune system, often referred to as a stealth character.

“Our research is into anything that you can put onto a device so that the body cannot sense it,” Scholz said. “You’ve got to make it so the body doesn’t even see it.”

She was involved in recent research that proved the in-vitro stability and non-toxicity of thin layers of customized block copolymers that coated tiny sensors, which were produced by a collaborator group at the University of Technology in Dresden, Germany. After further testing, the coated sensors could be implanted in patients to sense their blood glucose, carbon dioxide and serum pH levels. The coating uses a multi-layer concept that includes a hermetic sealing layer, a chemically inert innermost diffusion barrier for ions and humidity, and a surface layer of amphiphilic block copolymers.

Implanted into a patient beneath the skin, coated sensor data could be monitored wirelessly to control an insulin pump or monitor bodily functions to provide greater information to the physician treating a patient with respiratory problems. Since the coatings make the implants invisible to the immune system, the body doesn’t react to them as an invader and allows them to function.1

The recent work is an offshoot of Scholz’ involvement in developing biocompatible coatings for the Boston Retinal Implant Project, founded in the 1980s and supported by the Veterans Administration. The project has been successful in developing medical devices to restore some degree of vision to patients who have gone blind from retinitis pigmentosa or age-related macular degeneration. In that work, biocompatible coatings were needed to adapt retinal devices so that they would not be rejected while being used to deliver electrical signals to the brain and restore sight.

“I can make coatings for all sorts of implants,” Scholz said. “That’s our expertise, making these kinds of coatings. We can custom make them.”

And the applications for the coatings don’t stop at sensors and devices. “We can make coatings and ‘decorate’ them with delivery systems for various medicines,” Scholz said. “Physicians have told me that their biggest challenge with implanting devices is the trauma associated with surgery, which causes swelling. Swelling hinders healing. Loading the delivery systems with drugs that reduce swelling could be one way to speed up healing. Not only would these coatings make the device invisible to the body, they can also be used to help with the recovery process.

“All of these polymers, because of their chemical nature, lend themselves to drug delivery systems,” Scholz said. “All of this is really a neat chemistry.”

Scholz’ technique uses no heavy metals to catalyze the polymerizations. That sets it apart from other researchers, who work on similar polymer systems but often use heavy metals and then have to remove them during the process.

“I contend that if I do not put it in, I don’t have to worry about getting it back out,” she said.

Further advances in the work at UAH depend on finding funding for the research. “The ideas are there and we have the proofs of concept of the ideas, but we need the funding,” Scholz said. “I can draw out the chemistry for you and show you how it can be done, but all that costs money.”

For more information, visit www.uah.edu.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!