Recycling Pressure-Sensitive Products

The efficient control of contaminants such as metals, plastics, inks and adhesives during the processing of recovered paper products determines the profitability of recycling mills. In fact, it is arguably the most important technical obstacle in expanding the use of recycled paper.1-4 An especially challenging category of contaminants to manage is pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA). PSAs are soft elastomer-based materials that are highly viscous and sticky to the touch. In recovered paper, they are usually found as part of pressure-sensitive (PS) label systems, consisting of facestock coated with a 0.7-1.0 mil layer of PSA.

During the initial stages of the paper recycling process, the bonds between fibers are broken using water and mechanical energy. This operation, known as repulping, also fragments adhesive films. Much of the removal of these fragments in the recycling process occurs at the pressure screens and is governed mainly by the size and shape of the residual adhesive. The PSA that is not removed by screening is introduced into the remaining fiber recovery operations and the papermaking process, where it can significantly diminish production efficiency and product quality.5-7

A widely acknowledged approach to reduce the negative impact of PSA on paper recycling is to design adhesives for enhanced removal early in the recycling process. Given the high efficiency of particle removal demonstrated by screening operations, the most promising PSAs are those designed to generate larger residual particles.

Our recent research efforts have focused on developing guidelines for producing these types of PS products. This article includes the rationale for our test methods to gauge screening removal efficiencies, the identification of properties controlling the fragmentation of both hot-melt and water-based PSAs, and a discussion of the role additives and laminate design play in determining the fragmentation behavior of adhesive films.

MEASUREMENT OF PSA REMOVAL EFFICIENCIES

While mill trials would be the best way to determine which PSAs are problematic, they are expensive and the results are often difficult to interpret. Fortunately, the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) provided the resources required to test the same set of adhesives on a lab, pilot and mill scale.5 Based on the work sponsored by the USPS, a laboratory-scale test method has been developed by a subcommittee of the Tag and Label Manufacturers Institute (TLMI).8 These specification and test methods have been shown to correlate with other tests and are gaining wider acceptance.9

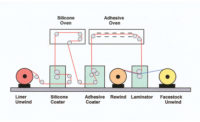

For this work, we have focused on Adirondack Plastic and Paper Recycling’s high-consistency laboratory repulper, and a gravity-flow flat screen from Valley Plastics and Paper Recycling. The repulper is equipped with a heating/cooling jacket and connected to a recirculating water bath to maintain temperatures during testing within ± 2°C of targets. The test requires only about 1.5 g of PSA film and an additional 300 g of conditioned paper, which includes the label facestock (~ 5 g), envelope-grade substrate (~ 8 g), and copy paper (287 g). Laminates and the copy paper are repulped for 30 minutes in 3 L of tap water, and the resulting fiber slurry is passed through the flat screen, which is equipped with a 0.015-in. slotted screen, wider than the 0.006-0.008-in. slots found in fine screens in typical fine paper recycling operations.

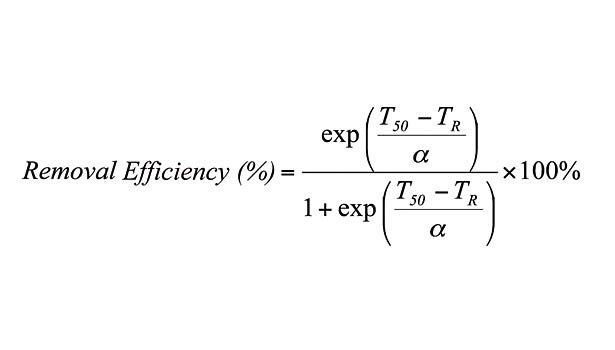

For this test, the amount of PSA rejected at the screen is measured gravimetrically. Screening rejects are composed of PSA particles, as well as cellulose fiber. The fiber is dissolved in copper (II)-ethylenediamine (CED), and the adhesive particles are isolated via filtration and dried at 105°C to a constant weight. Rejected PSA mass is reported as a removal efficiency, which is the percentage of PSA mass added to the repulper that is rejected at the screen. Tested PSA films are soaked in CED aqueous solutions and dried at 105°C for extended periods to determine the mass loss of PSA additives (e.g., emulsifiers and tackifiers) during the analysis. Losses are usually found to be negligible. The details of this procedure are available elsewhere.10,11 Reproducibility of removal efficiency measurements was determined to be ± 3-4%.

OPTIMIZING THE REMOVAL OF PSA FILMS

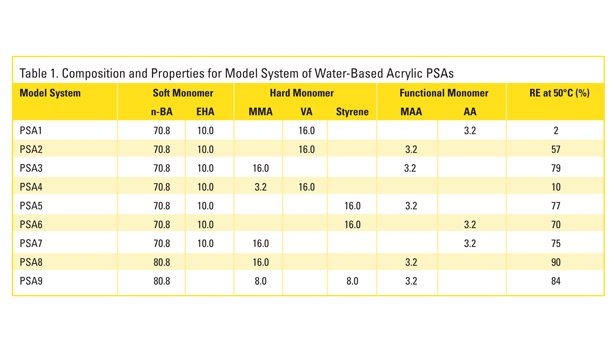

Water-based acrylic PSA dominates the PS label market and, along with hot-melt PSAs, composes most of the PSA used to produce labels.12 By providing guidelines for making these two types of PSAs more recycling compatible, the majority of adhesives presented to recycling mills could be reformulated.

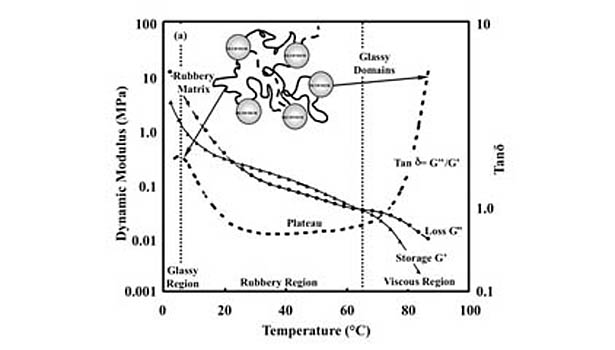

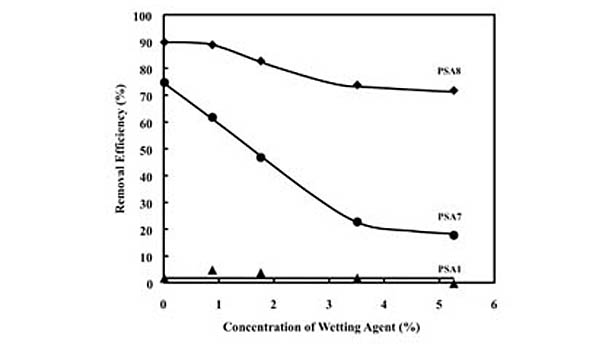

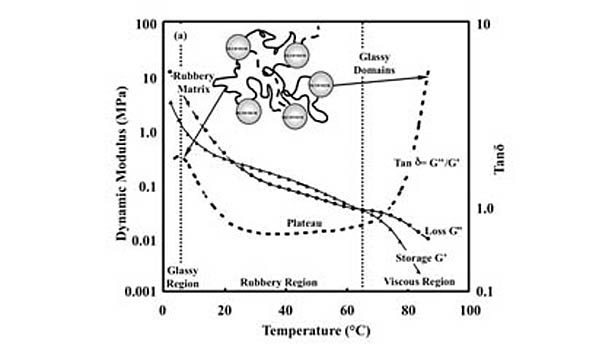

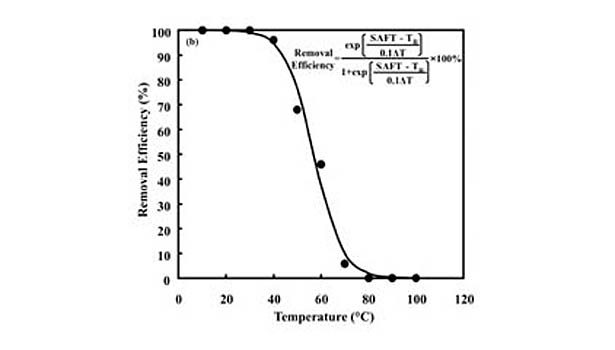

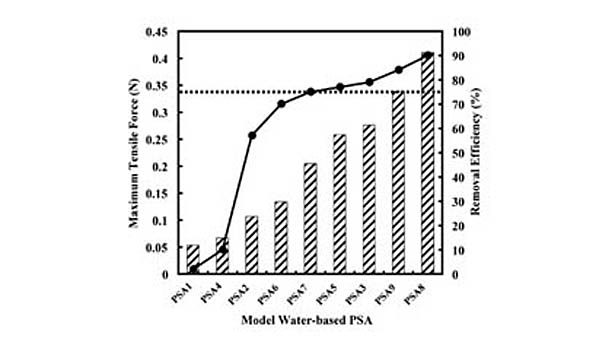

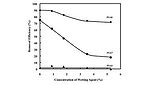

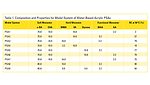

Hot-melt adhesives have phase transitions near typical recycling temperatures. If the repulping temperature is high relative to these transitions, the adhesive is soft, allowing it to break down more easily and form smaller fragments. The fragmentation of a water-based PSA is controlled by its strength in aqueous environments. This is determined in large part by its water resistance, which is reduced by the presence of surfactants, which are needed for synthesis and formulation, and the greater polarity of the adhesive polymer. In general terms, the fragmentation of hot-melt PSA films is controlled by temperature, while the residual strength under high moisture conditions controls the fragmentation of water-based adhesive films.

The goal is to limit the extent of PSA fragmentation during repulping operations. The focus is on the films themselves, so additives and laminate designs are held constant for most of the tests reviewed here to provide for direct comparisons. As will be shown, relatively minor modifications (that do not compromise performance or costs) can be used to substantially increase the screening removal efficiencies of PSA films.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!